The Early Days

Before Louisville was even a city, the Ohio River and its tributary streams were important natural features of this area. The Ohio River was crucial for transportation and trade, and the abundance of local streams provided water that was essential for agriculture and daily living. The local waterways were a key reason why this area was attractive to early settlers.

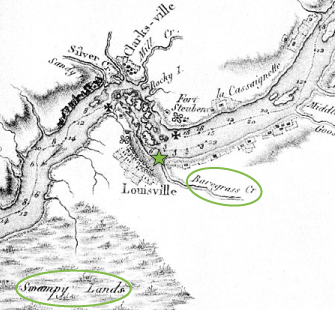

The map below from 1796 shows the growing city of Louisville, alongside the Ohio River, where there were numerous streams, ponds and “swampy lands” in the area. This map also shows where Beargrass Creek used to enter the Ohio River, at a point where the Galt House sits today.

Because there were no waste management systems in place, it was common for settlements near water—like the new city of Louisville—to dispose of their garbage and sewage directly into nearby rivers, streams or creeks. In addition, garbage and refuse that had been left in streets or other flat land areas would make its way into waterways, especially during rainfalls. As more people moved into Louisville, they created more garbage and waste. This waste ended up in the creeks and streams, making the waterways polluted.

When the creeks, streams and ponds became polluted, people started getting sick from using and living near the water. Polluted water tends to have bacteria that can make people sick, and stagnant water is also an ideal environment for disease-carrying mosquitoes to breed.

Although city officials weren’t exactly sure what caused the increase of diseases, such as malaria, cholera and typhoid fever, people suspected the polluted streams and ponds as the source of these illnesses. All of these issues became a big challenge for the city, so the management of wastewater and stormwater became a priority. At Louisville’s request, the Kentucky legislature passed the “Hog and Pond Law” in 1805 to ban pigs and hogs from the streets and to drain the water from stagnant ponds.