Problems with the Morris Forman plant continued to challenge MSD in the 1990s. While the plant met federal and state standards most of the time, it still exceeded pollution limits too often — especially in wet weather, when stormwater boosted the flow beyond the plant’s 105 million gallon-per-day capacity. In addition, odor problems affected nearby neighborhoods.

In 1991, an outside engineering firm was hired to prepare a comprehensive "action plan for the ’90s" for the plant, eventually recommending millions of dollars of additions and improvements to meet federal pollution standards and reduce odors.

Experience with one of these improvements would bring back memories of the problems of the 1970s. In December, 1994, a $13.2 million pair of bioroughing towers, which help digest organic waste in the water, went into operation, and the plant’s performance improved. A year later, one of the towers collapsed, and the other was shut down as a precaution. Work on rebuilding the towers’ interiors wouldn’t start until 1998.

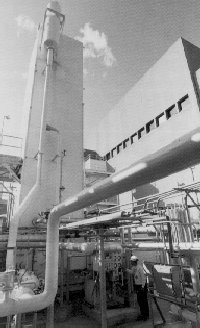

Two innovative improvements were designed in the mid-1990s. A "biofilter," which uses natural processes to digest and remove the substances that cause odor, was installed at one of the main structures leading into the plant. And an energy-producing plant to process the solids removed from wastewater was being planned; it would burn the gases produced in treating the solids to power its own machinery and generate electricity for the Morris Forman plant.

The West County plant has always bettered federal clean-water standards by a wide margin. By the mid-1990s, however, it was approaching its capacity as its service area expanded. In 1994, it was added to the Morris Forman plant’s "action plan for the ’90s," because the two plants together were designed to handle most of the community’s wastewater.

MSD Photos by Martin E. Biemer

‘Bio-solids’: a long-wasted resource

One of the most persistent puzzles facing MSD over the years has been finding a way to use the waste removed from wastewater.

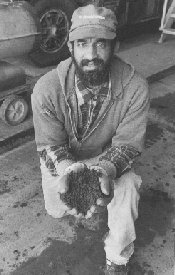

The waste, called bio-solids (or sewage sludge), is the concentrated solid matter left after the treatment process. It is rich in organic material and nutrients. Properly treated, it can become a useful soil conditioner and fertilizer.

Other large cities have recycled their waste this way. But, beginning in the early 1970s, several plans to process MSD’s solids for re-use have failed. They included a mid-1970s plan to sell the solids to a private firm to turn them into fertilizer; a late-1970s plan to use the solids to help reclaim strip mines; and a mid-1980s plan by farmers in Shelby and Spencer counties to use the solids for fertilizer.

There have been two main obstacles to carrying out these plans: the possibility of contaminants in the waste, and public perception.

MSD Photo by Martin E. Biemer

MSD’s large volume of industrial waste, and the community’s history of hazardous material spills, were responsible for the first obstacle. As the industrial pretreatment program gathered momentum in the 1980s, the concentration of hazardous materials in MSD’s waste decreased. By the mid-1990s, MSD’s solid waste met the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s standards for "clean" class A sewage bio-solids.

The other obstacle — public perception — has been more difficult to overcome. Objections have ranged from concerns about odors, to general objections to storing and processing waste in certain neighborhoods — or in entire counties.

The alternatives have been few: burn the solids, or bury them. Unfortunately, the incinerators at the Morris Forman plant, installed in the early 1970s, proved difficult to operate efficiently. The major problems were the heat content of the solids, and increasingly stringent air pollution control regulations.

The result: for decades, the potentially valuable resource has been buried in landfills.

In 1996, MSD decided to eliminate the old Zimpro processing facility, which could generate strong odors as it cooked the solids to sterilize them. There were two major goals: to minimize odors, and to find some way to use the long-wasted resource.

One alternative seemed to offer great promise: it would produce gas which would be used as fuel for gas turbine engines, which in turn would be used to generate electricity. The final product, clean solids, could be used without further treatment as a soil conditioner. Efforts in this area were continuing in late 1996.

As MSD began its second half-century of service, the Board and the staff were still working to solve one of their most persistent puzzles: finding an economical way to put the solids removed from wastewater to good use.

MSD History continued - Infrastructure Rehabilitation