In 1948, Louisville’s first television station (WAVE-TV) went on the air, Louisville’s occupational tax went into effect, and black citizens were admitted for the first time in the downtown public library.

That same year, the eight states in the Ohio River Valley joined the federal government in an interstate compact to clean up the river, which had become a 981-mile open sewer for untreated municipal and industrial wastes. The new Ohio River Valley Water Sanitation Commission (ORSANCO) went to work immediately. In September, the Kentucky Department of Health informed MSD that, under the interstate compact, MSD would be required to build a sewage treatment plant and stop discharging untreated wastewater into the Ohio River.

The need for a treatment plant had been discussed since the 1930s, so the news came as no surprise. But the interstate compact, with its strong enforcement powers, added a sense of urgency that had been lacking in the past.

There were two major problems: financing and priorities. As the Louisville Courier-Journal would report five years later, MSD was spending about 70 percent of its money in those early years for storm sewer work (mostly along the old combined sewer system). But all of its income was from charges for sanitary sewer service.

Financing sanitary sewer improvements and drainage would become matters for sometimes bitter debate for the next four decades. Juggling priorities would become as ticklish as juggling balloons full of wastewater.

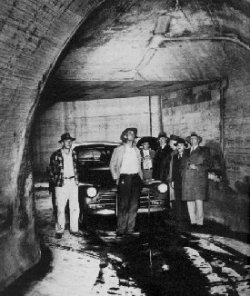

Courier-Journal and LouisvilleTimes Photo by Cort Best

The Treatment Plant

Early in 1950, MSD began acquiring land for the new treatment plant. It was the site of Fort Southworth, a never-completed Civil War fortification just outside the city limits at Algonquin and South Western parkways.

But as design work continued, the cost estimates increased — eventually to $12 million. MSD’s rates weren’t enough to finance construction, and the agency asked the city for help. The city, which had intended to turn all of these problems over to the new agency in 1946, balked. But the Board of Aldermen and the mayor also balked at approving the 40 percent rate increase MSD would need to finance the plant by itself.

In 1951, ORSANCO stressed the urgency of starting work on the new plant. In early 1953, the Kentucky Water Pollution Control Commission briefly ordered a halt to all new sewer construction in the Louisville area until there were definite plans to build the new plant — in effect, a moratorium on development.

Later that year, the compromise was reached: the City of Louisville would borrow half the money for the new plant — $6 million — and MSD would borrow the other half.

Construction work finally started at the plant in 1956. Two years later, construction started at the Southwestern Outfall pumping station, which would pump wastewater from the system’s largest sewer line to the new plant. And in 1958 — more than ten years after that first notification from ORSANCO — MSD’s first treatment plant went into operation; the pumping station was completed the next year.

Sanitary Sewer Expansion

While the treatment plant issue was being debated, suburban expansion was booming. MSD had the authority to serve the entire county, but it was still struggling with the challenge of serving the unserved areas of the city. A compromise was reached in the early 1950s: the Board of Health would allow individual septic tanks where the land could accommodate them, and require small, "package" sewage treatment plants where septic tanks wouldn’t work well. The board emphasized that both of these measures would be considered "temporary," and would be replaced by MSD service when MSD sewers became available.

This compromise would be another long-simmering source of controversy; many of these "temporary" facilities would still be in use more than 40 years later.

Inside the City of Louisville, the situation was somewhat different. The city and MSD had set a goal of providing sanitary sewers for the entire city. By early 1956, the cost of doing this — and building new interceptor lines to lead to the new treatment plant — was estimated at $40 million. There was also a large additional cost for serving the areas being annexed to the city.

Here, too, there was a historic compromise: owners of properties getting sewers for the first time would have to help pay for the cost of building them. This slowed the program in many neighborhoods, as some property owners balked at the cost of building new sewers.

In one major suburban development, however, the conditions and costs were worked out quickly. In early 1951, when General Electric announced it would move its entire home appliance manufacturing operation to a new 1,000-acre industrial park near Buechel, company officials began negotiating with MSD for sewer service. In early 1952, an agreement was reached: MSD would spend $2.6 million to extend sewer lines to Appliance Park; GE would repay $1.9 million over the next 20 years. The agreement helped give the community a major new employer — but it also diverted $2.6 million that had been earmarked for the treatment plant and sewer improvements.

MSD History continued - Drainage