Drainage programs were a continuing puzzle, and a continuing controversy. In unincorporated areas of Jefferson County, the county still hired MSD to handle its drainage program, but progress depended on county appropriations. Each new suburban city that incorporated found itself immediately responsible for its own drainage program. Other government agencies were responsible for drainage on their land: the state highway department, the airport authority, the city-county parks department, the state parks department. While each government agency was responsible for drainage within its own boundaries, no government agency had the responsibility, or the authority, to make sure these drainage programs worked well together.

One major advance during the 1970s was the construction of the dry bed flood control basin on the south fork of Beargrass Creek near Houston Acres; it would keep heavy rains from aggravating the already serious flooding problems in the downstream suburbs and the City of Louisville.

But in the city itself, the dispute over the responsibility for drainage became bitter.

Basically, the argument was the same as it had been. City officials said responsibility for drainage had been turned over to MSD when the agency was formed, because the old city sewer system handled both sewage and drainage. MSD argued that it had no source of income for drainage improvements, because federal laws said that money collected for sanitary sewer service had to be used for sanitary sewer service.

In 1978, a consulting firm hired by MSD recommended that the city be responsible for maintaining and improving the drainage system. It recommended that the money be raised through a variety of sources, such as a drainage service charge, property taxes, and/or occupational taxes.

The report also said that MSD would spend $2.3 million in its income from sewer fees to maintain and operate the city’s drainage system in 1978 — and about $600,000 in money from county government to maintain the county’s system.

And it estimated that the cost of needed drainage improvements in the city would be $63 million.

City government took no action to provide financing for drainage services. But in 1979, it went to court to ask that MSD be declared solely responsible for drainage in the city.

While the drainage issue had reached crisis proportions in the city, poorly regulated suburban development was creating increasing problems outside the city.

Finances

Rising inflation in the mid-1970s affected the entire nation, and rapidly reduced the buying power of MSD’s rate increases of the early 1970s. At the same time, federal clean water rules were requiring costly improvement programs. And federal rules were requiring that sewer rates be written so that users shared the costs more equally.

The last rule ended a benefit local government agencies had enjoyed for years: free sewer service. Louisville city schools had to begin paying sewer bills after they merged with the county school system. City and county governments were supposed to begin paying in 1975; city government started paying in 1976. (To help offset city government’s sewer charges of about $400,000 per year, MSD took over the $180,000-per-year payments on the city bonds that were issued to build the original treatment plant, later named for Morris Forman.)

And in 1977, MSD proposed rate changes that would increase its total income by about 50 percent. Industrial rates would increase far more than commercial and residential rates, to meet the federal demand that all users pay their fair shares.

At the time, the Louisville Board of Aldermen and Jefferson County Fiscal Court still had to approve any MSD rate increase. The Board of Aldermen refused to act until MSD took responsibility for the city’s drainage program.

As the dispute continued, MSD’s reserve fund dropped and dropped — below the level allowed by the terms of the $58 million bond issue of 1971. As a result, one of the major investment advisory services lowered MSD’s credit rating, and a second service was examining the situation.

The implications were sweeping. The lower rating not only would make it more expensive for MSD to borrow money; it could affect the credit ratings of city and county government, as well.

MSD and the aldermen reached a tentative compromise in early 1978. MSD would agree to take responsibility for the city’s drainage program, using money that would be returned later when a way to finance the drainage projects was found. MSD also agreed to undergo a management study, and to conduct a study of the city’s drainage needs.

The compromise didn’t hold up, and the aldermen delayed MSD’s proposed rate increase in 1979. The problem with bond ratings also continued.

Finally, in October, 1979, a broader compromise was reached. It preserved local government’s credit ratings, and would make it much easier for MSD to keep up with inflation in the future. Basically, MSD would be allowed to increase its rates whenever the money it had available to repay its bonds fell below 110 percent of the amount that would be required to make the payments. The Board of Aldermen and Fiscal Court would have to give their approval only if the total amount of the rate increases would top more than 7 percent in any one-year period. A long series of rate-related crises appeared to be over.

The 'seven percent solution' to decades of financing problems

MSD's chronic financing problems were mostly resolved in 1979 through a plan that came to be known as the "seven percent solution." In the future, MSD could increase its rates by up to seven percent in any one-year period without approval by the Louisville Board of Aldermen and Jefferson County Fiscal Court — if the money MSD had available to pay its outstanding bonds fell below 110 percent of the amount required to make the payments.

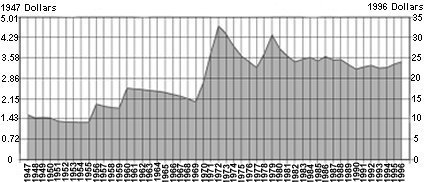

The graph below shows the effects of decades of rate disputes, and the seven percent solution, on the bimonthly bill paid by a typical residential customer. To show the effects of inflation, the bills have been adjusted to 1947 and 1996 dollars using the U.S. Consumer Price Index.

Basically, inflation reduces the effective rate until an increase goes into effect; this was especially troublesome during the high-inflation 1970s. The small 1981 increase — the first after the solution went into effect — wasn't even enough to keep up with inflation. Since 1982, the bimonthly bills — adjusted for inflation — have hovered around and under $25 in 1996 dollars ($3.58 in 1947 dollars).

Typical MSD residential customer's bill every two months, adjusted for inflation

MSD History continued