When Person took office, MSD’s challenges were like a multi-layered jigsaw puzzle: one layer for sanitary sewers, another for drainage, and several for financing. As the suburbs multiplied, the pieces of the puzzle divided. There were many people, with different viewpoints, working to solve the puzzle in their own different ways: state and federal water quality agencies; the Louisville mayor and Board of Aldermen; the Jefferson County judge and Fiscal Court; state legislators; elected officials of the growing number of suburban cities; the Board of Health; the Chamber of Commerce and other business groups; neighborhood associations . . . .

The complexity of the puzzle can be illustrated by the Pond Creek drainage improvement proposal of the 1950s and related developments.

Much of the Pond Creek area, in southern Jefferson County, was a wetland — ponds and swamps — that had been converted to farmland in the late 19th and early 20th centuries by digging a network of ditches. In the post-World War II housing boom, the inexpensive flat land near the city became attractive to developers.

Court decisions kept local officials from limiting construction in these wet and flood-prone areas. By the middle 1950s, the area was filling with suburban housing and the drainage problems became even more severe.

Jefferson County had responsibility for drainage, but not enough money for much more than routine maintenance. In 1956, the legislature passed a law allowing the county and MSD to establish drainage districts, and to tax the property owners in those districts to finance drainage improvements.

In 1958, MSD completed a plan to improve drainage in the Pond Creek area. The plan covered about 92 square miles, and would cost about $1.5 million. Property owners would be charged about $25 an acre.

The Pond Creek Objectors Committee, with signatures of 1,000 landowners and residents, challenged the plan in court. And the City of Louisville, which included a little more than three square miles of the area, said the priority should be on sewers, not drainage.

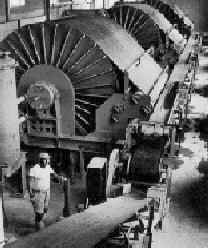

Courier-Journal and Louisville Times Photo

In 1960, while the challenge was wending its way through the courts, heavy rains caused widespread flooding in the area. County Judge B. C. VanArsdale blamed the protesters, saying the delayed plan could have reduced the damage substantially.

After more flooding in 1961, Fiscal Court decided to abandon the court battle, and contracted with MSD to make simpler drainage improvements in the area.

Courier-Journal and Louisville Times Photos

The heavy rains of 1960 and 1961 also caused street and basement flooding in Louisville. MSD said nearly all of its revenue was committed to paying for sanitary sewer service and treatment; only minor amounts were available for drainage improvements. The city, MSD said, would have to finance major drainage improvements.

And in 1961, MSD and Jefferson County government told the proliferating suburban cities outside Louisville that they were responsible for their own drainage programs.

While the problems mounted, the community seemed to agree that MSD needed more money to attack them. In early 1960, the Board of Aldermen approved a rate increase of about 40 percent — only two-thirds of the amount MSD had requested. The cost of living had increased 10 percent since the 1956 rate increase.

The Bold Plan

As the drainage problems became more critical and complex, sanitary sewer problems were also worsening. In 1959, the Board of Health banned new septic tanks in the area drained by the Middle Fork of Beargrass Creek, the prime suburban development area between Taylorsville and Shelbyville Roads east of Cherokee Park and St. Matthews. Soon afterward, it banned new septic tanks in a large area of southwest Jefferson County. Polluted water from septic tanks was creating a health hazard in ditches and streams. For the first time, all new developments in these areas would have to have sewers.

In October, 1961, the Republican candidates for Louisville mayor and Jefferson County judge — William O. Cowger and Marlow W. Cook — proposed a bold plan that would pull all of the pieces of the puzzles together. The plan was to merge MSD and the Louisville Water Company; give the merged agency countywide responsibility for water, sewers and drainage; give it the authority to charge fees and levy taxes for its services; and govern it with a non-partisan, elected board, similar to a school board.

The Chamber of Commerce and the Courier-Journal and Louisville Times supported the plan, saying it would provide much-needed countywide services at last. Cowger and Cook were elected that fall, and sent the plan to the 1962 legislature.

The battle was fierce and partisan. The plan was amended, watered down, and virtually killed. All that emerged was a law allowing Jefferson County to set up its own sanitation district, a solution which soon proved to be unworkable.

MSD History continued - The Compromise Plan