The war ended in November, 1918. A year later, Louisville’s voters approved another $2 million bond issue for new sewers, and the second Commissioners of Sewerage were organized to oversee the work.

This group would design and build dozens of miles of major new sewers through the boom years of the 1920s and the Depression years of the 1930s. As the Depression wore on, the Commissioners also managed sewer and drainage work done under federal public works programs.

Most of the local financing came from bond issues: the original $2 million, another $5 million approved in 1924, and another $10 million approved in 1928. These were all "general obligation" bonds, which the city pledged to pay back out of future tax revenue.

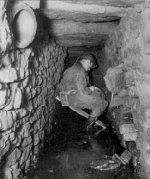

The work included miles of interceptor sewers that kept raw sewage from flowing directly into Beargrass Creek; miles of relief sewers to handle the excess water from overloaded older sewer lines; and the huge Southwestern Outfall, stretching from South Louisville to the Ohio River near Paddy’s Run.

Another project was the city’s first sewage pump station, built to serve the low-lying "point" area between the old course of Beargrass Creek and the river. The river level in downtown Louisville had been raised eight feet when the Ohio River dam was rebuilt in the 1920s, permanently flooding some of the old sewers and causing the water to stagnate. The station, completed in 1939, pumped the wastewater from the point area into the Beargrass Creek interceptor.

The Commissioners’ work also included construction of miles of concrete channel which replaced the natural course of Beargrass Creek, increasing its capacity to carry stormwater to the Ohio River.

The money from the bond issues ran out as World War II began. Civilian construction was curtailed because of the war effort. The Commissioners planned to go out of business in 1942, and issued their "final report" that year, but it took another two years to tie up the loose ends.

The Commissioners of Sewerage final report listed the daunting challenges still facing the city sewer system:

- Many new sewers were urgently needed.

- Many old sewers needed repairs or replacement.

- A sewage treatment plant would have to be built.

- Maintenance of the existing sewer system would have to increase.

- Continuing pollution of Beargrass Creek would have to be studied, identified and stopped.

- Stormwater outlets along the streams would have to be checked, to make sure they weren’t discharging raw sewage into the streams during dry weather.

- Major improvements would be needed to reduce the extensive flooding of streets and basements during and after heavy rains.

- Major changes in the sewer system would be required when the Ohio River floodwall was built, to keep river water from flowing backward through the sewer lines and under the floodwall.

- And most importantly, in view of the slow progress of previous generations, a systematic and continuing method of financing all this sewer work would have to be devised. City tax revenues were simply not enough to do the job.

A Troublesome Heritage: The Combined Sewer System

One of the most troublesome problems passed on to MSD was one that the Commissioners of Sewerage had considered a good solution: combined sewers.

Combined sewers carry both wastewater and stormwater in the same pipes. The design evolved from the first ditches built in the 1820s, and was commonly used in cities throughout the Midwest and Northeast.

Separate systems for wastewater and stormwater started developing in the 1920s, but the Commissioners of Sewerage didn’t like them. They thought it was too hard to make sure the connections were made to the right systems. Their final report said it was better to collect everything in one set of pipes, so the wastewater and storm-water could be dealt with together.

The problem with this policy was that the pipes couldn’t carry the flow. During heavy rains the combined sewers became overloaded. The interceptor lines spilled their mixture of stormwater and wastewater into the streams — through "combined sewer overflows" designed for the purpose.

The theory went like this: during dry weather, the wastewater was kept in the pipes; during wet weather, the stormwater would dilute the waste going into the streams. In practice, the combined sewer system did reduce stream pollution — but the overflows still dumped raw sewage into the streams, sometimes throughout the year.

There was another problem, as well. When combined sewers were overloaded with stormwater, the polluted water often backed up into basements. This was a major challenge facing the sewer system when MSD was established, and would continue to be a major challenge into the late 1990s — when more than 600 miles of combined sewers remained.